19. My Concussion Recovery: One Step Forward, Two Steps Back

/A Taste of Activity

After the small breakthrough with my headaches, I decided to use it as an opportunity to push myself a little further. Dr. Kutcher had advised me to begin incorporating exercise back into my life once I started seeing progress, and as much as the idea terrified me, I knew I had to at least give it a try.

The hope was that by pushing through some of the pain, my body would adjust and build up a tolerance for activity. Whenever I tried to do this in the past I had failed miserably. My symptoms would dramatically increase and it would take me days, sometimes even weeks, to return to a more tolerable baseline of symptoms. Yet that Sunday afternoon on my way home from Boston, that pattern broke. It was as if my system reset itself temporarily, which was the lucky break I had been looking for since I got hurt.

So I decided to start by riding the stationary bike – ten minutes everyday for at least one week. I’d record my symptoms everyday under a notes page on my phone.

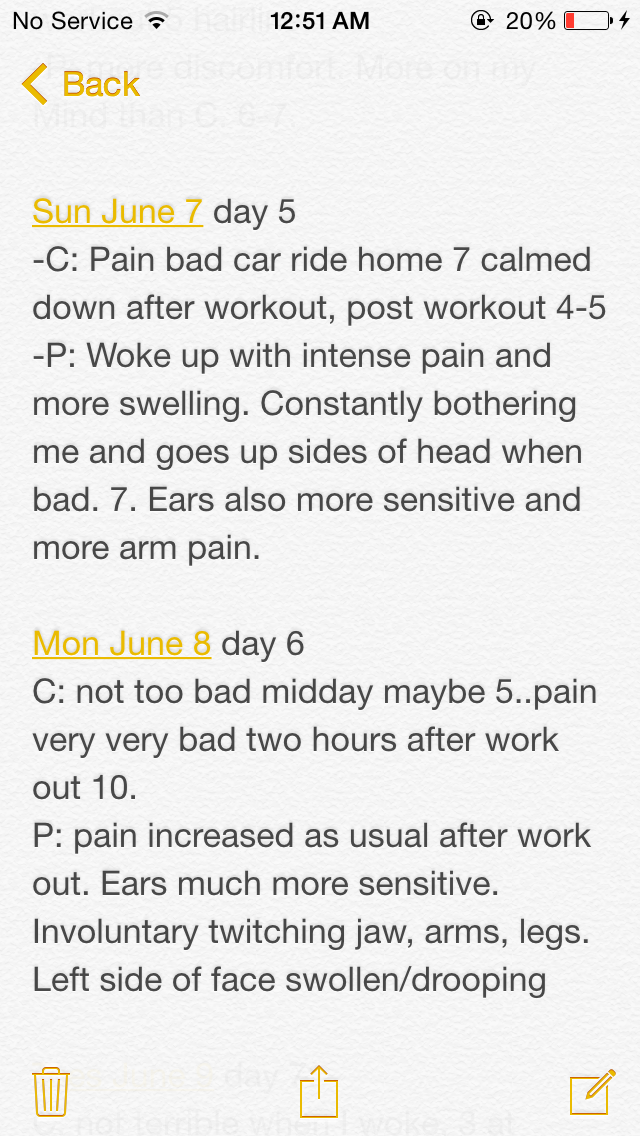

"C" refers to my concussion symptoms, and "P" stands for the prolotherapy related symptoms.

Because my symptoms always worsened with exercise, I decided to hop on the stationary bike in the evenings. That way, when my symptoms got worse I could lie down and spend the remainder of the night in bed recovering.

Unfortunately, things didn’t turn out as I had hoped. My trial period lasted nine days before my symptoms became so intolerable I had no choice but to stop. My existing symptoms significantly worsened – headaches, excruciating pain radiating down my arms, noise sensitivity, and visual disturbances. Symptoms I thought had gone away for good returned – involuntary twitching, sensitivity dysfunction, Bells Palsy/facial drooping and swelling. And new symptoms appeared: sensitivity to taste and smell (which luckily only lasted a day or two), and excruciating pain in my feet that made me limp (which persisted).

It was so scary and frustrating that it was almost comical. Activity was everything for me. Exercise – the movement, the endorphins, the sweat, the push-it-to-your-limit pain – I loved all of it and missed it more than I could ever say.

Yet somehow my body lost itself every time I tried being active. It felt so confused. It was as if something in my brain – the most fascinatingly complex and intricate organ in the body – had gone awry and lost its way. Luckily, a two-week trip back to Michigan was only a few weeks away, and I was very eager to find out what was going on.

The Nervous System

What I did know for certain until then, however, was that my nerves were malfunctioning. Before this experience, I only used or understood the term ‘nerves’ in the context of emotions like anxiety and anger.

This is the best image i've come across that depicts the pain in my head. Imagine those green wires (nerves) violently constricting inwards - at all times. This sensation began happening all over my body after the prolo injections.

And apart from a course or two in biology, I never really took time to learn the role nerves play in the body. These small whitish fibers transmit impulses of sensation to and from the brain and spinal chord to the rest of the body.

Nerves are the reason I’m able to use my fingers to type on my laptop keyboard, to feel when something is hot against my skin, and to perform the everyday functions that, as humans, we need to survive. I think of nerves as hidden brilliance. They are constantly working in the background, performing the most complex involuntary functions that most of us never give a second thought to.

When nerves aren’t functioning properly, however, they aren’t so hidden and brilliant. They have the power to wreck havoc on an injured body, which is exactly what happened to me when I got my concussion and later developed these odd nerve malfunctioning’s after the prolotherapy injections.

Before I go into more detail about my experience with nerves, I’ll highlight a few key divisions of our nervous system below:

There are two main parts to the nervous system: the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system. The central nervous system consists of our brain and spinal chord, while the peripheral nervous system includes the nerves and ganglia in our extremities. Information is constantly relayed between the central and peripheral nervous systems, which is how we are able to function.

A key part of the peripheral nervous system is the autonomic nervous system, which controls involuntary bodily functions such as breathing, digestion and heart rate. The autonomic nervous system has two main branches: the sympathetic and parasympathetic. Our sympathetic nervous system is referred to as our “fight or flight” system, while the parasympathetic is known as our “rest and digest” system. Think of adrenaline and physical exercise for sympathetic, and meditation and relaxation for parasympathetic.

Sympathetic Mediated Pain

Both Dr. Kutcher and Dr. Colwell believed that my issues were stemming from the sympathetic “fight or flight” part of my nervous system. They concluded that my nervous system was in an overregulated state and was producing sympathetic mediated pain and symptoms.

One syndrome akin to this experience is Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy (RSD). It results when your sympathetic nervous system (the “fight or flight” system) responds excessively to a trauma to the body; causing your body to freak out over something it shouldn’t freak out over. It can affect both your sensory and motor nerves, causing symptoms that include pain, swelling, tingling and burning sensations, muscle twitching, tremors, muscle spasms, and more. Usually RSD happens after trauma to the limbs, but in my case the exaggerated response came as a result of the prolotherapy injections in my neck.

My doctors believe the concussion I had suffered made me more susceptible to this type of abnormal sympathetic response for a couple of reasons.

First, concussions alter brain function. When trauma to your brain occurs, it can shift chemicals around and trigger various underlying issues, making you more susceptible to certain abnormal reactions.

One common scenario for concussion patients is the triggering of an underlying inattentive disorder. In other words, a patient may have the genetic make-up for ADD or ADHD, but may not experience any noticeable or severe symptoms of it until a concussion occurs. A concussion can trigger this abnormality in the brain and make it much more pronounced than it otherwise would have been.

A close friend of mine experienced this exact scenario: she always believed she had a minor inattentive disorder but got along just fine with it until she suffered a concussion. Now, she struggles daily with intense concentration issues.

A similar type of scenario likely happened to me, except instead of triggering an inattentive disorder, the concussion may have triggered an increased susceptibility to a nervous system malfunction similar to that of RSD.

Another factor that may have made me more susceptible to this is the fact that my nervous system was already in a heightened state due to the unresolved injuries to my neck, which was was driving this hyperactivity.

Sixteen prolotherapy injections would be a lot for a normal person, but it was certainly way too much for someone with nervous system sensitivity and whose body was fighting off an injury that was worsening. My body perceived the injections as a threat, triggering the “fight or flight” sympathetic response and overwhelming my normal coping mechanisms for handling trauma. As a result, the muscles surrounding the injection site violently constricted in protest, which compressed my nerves and produced all my new, crazy symptoms.

It had been the final straw, and it did me in.

The Plan

The plan moving forward was virtually the same as it was before this discovery (with some added components): I had to break the chronic pattern of nerve firing and subsequent muscle tension that my body had fallen into. When muscles are tight, it causes the nerves to fire and when these nerves emit such pain signals, it triggers the muscles to tighten further. It’s a vicious cycle, and one that’s not easily broken.

The second complicating factor (which I learned later at a different concussion program) is that when your muscles are chronically tight it causes them to fatigue. When your muscles are weak, they tighten even further, perpetuating the already daunting pain-ridden neuromuscular cycle.

It was an uphill battle, but one I was ready for.

Dr. Colwell added several new stretches and strengthening exercises to my rehab regimen, and Dr. Kutcher increased the dosage of the medication meant to stabilize nerve membranes and limit signal firing. The hope was that this combination of treatment would break this debilitating cycle: the stretching would release the muscle tension all over my body, and the medication would control the nerve firing. With time, this plan would calm the sympathetic “fight or flight” response and eventually break the pattern.

I wanted to explain all of this in detail for two reasons:

One, I find it very interesting. And two, understanding exactly what was happening with my body was incredibly important for me throughout the healing process. When I didn’t know what was going on I felt lost and helpless, which fueled anxiety. Once my issues were clearly articulated to me and I was given a treatment plan to address it, I was ready to roll.

It is this absence of understanding and clear-cut path forward that far too many concussion sufferers are missing. It makes my heart ache because I know there are answers to their struggles that they simply aren’t getting. This is why I’m sharing my story.